SiteSection, Part II

Sullivan Swamp, Quebec Branch-Wilson Creek Confluence Bog.

A Southern Appalachian Shrub Bog

Everything changes.

Some of this change we can observe, some we cannot. Butterflies deposit eggs that hatch into caterpillars that eat, grow and transform into a chrysalis before emerging as a butterfly. The cycle continues throughout the seasons, as do cycles of growth, renewal, and regeneration in all living and non-living systems. Mountains are born of earth's tectonic activity. Continental collisions, and even gentle and slow uplifts of the land, give us mountains. Water, wind, light and gravity chop these mountains down...they slowly crumble from their great rocky heights, their surfaces eroded and material transported down creeks, rivers, to bays and oceans...giving birth to quartz sand beaches...everything changes.

Regardless of where and when you stop to observe change, you will get a snapshot in time that is unique to that place and moment, never experienced before, and never to be experienced again. For me, this is the wonder of actively engaging the details of the world. There is always something new, and the more one inquires, the more one learns about their place, their role, as a mammal within nature.

The following is a snapshot of our August 24-26, 2012 exploration of Sullivan Swamp:

August 24-25, 2012 species list: (SPECIES LIST LINK)

Interactive map of the bog: (INTERACTIVE MAP LINK)

Gallery of Photographs: (PHOTOGRAPHS LINK)

On the weekend of August 24th

, Blue Ridge Discovery Center (BRDC) returned to Sullivan Swamp for its second survey effort of the year. With the funding support of the Harris and Frances Block Foundation, and in cooperation with the Department of Conservation and Recreation and Grayson Highlands State Park, BRDC’s

program and its staff and participants explored one of Virginia's finest ecological treasures. The ecosystem is classified as a southern Appalachian shrub bog, of which there are only about 30 on the planet! There are at least two occurrences of this ecosystem at Grayson Highlands State Park, and these bogs are the largest of those documented to date, covering between 8-10 acres each.

An account of the survey

With the idea of seasonal change in our minds, we entered Sullivan Swamp for the second time this year. One month has passed since we last visited and the changes in the bog were readily noticeable, from the bloom of the flowers to the buzzing of the insects, from the variety of birds to the change in the air temperature. It was clear that we were going to encounter species we had not yet documented.

Nighttime survey

The adventure began with what was our first attempt at a SiteSection nighttime survey. Staff arrived early to prepare equipment and and by 8pm the full crew was ready to begin. The evening began with a light rain and overcast skies. The damp evening beckoned the bog to present itself differently than if it had been a clear starry night. Just to the east were towering thunderstorms. All in all, at a location known for its dramatic and sudden shifts in weather, we lucked out.

The dampness put a bit of a damper on our nighttime insect inventory. Attracted to our lights and the sheets that glowed before them were a sparse array of very small insects. The low species numbers allowed participants time to practice and perfect their macro-photography techniques. Among the critters attracted to our lights were a yellow-dusted cream moth, sharp-angled carpet moth, and countless leaf hoppers. A couple of spiders set up camp near the lights to take advantage of the platter of tiny insects.

Between stints of documenting the critters attracted to the night lights the survey crews branched out into the bog with headlamps, cameras and nets. The light rain coaxed amphibians from the streams and we were afforded excellent looks at black-bellied and Blue Ridge dusky salamanders in a variety of developmental phases. The Blue Ridge dusky is on the decline, rare in parts of its range, and is in need of moderate conservation. It was the most common salamander observed on this night in the streamlets of bog.

As the night progressed and the rains ceased the chorus of katydids grew. From that chorus an unusual call could be discerned. What it was, we do not know. The hypothesis is that it was a frog. Scott Jackson-Ricketts heard it best of all, and his keen ears tell him that it was not a familiar tune. The possibilities for what species it could have been have been narrowed to upland chorus frog and mountain chorus frog. Further inquiry will be needed to confirm the occurrence, but as of now the sound heard is closest to the mountain chorus frog

. This would be yet another significant discovery, as the species has not been officially documented in Grayson County before (

). It is also considered to be a species of very high conservation need, as it is at risk of extirpation or extinction. The nighttime survey wrapped up at 11pm, with all participants exhausted and wet. Everyone retired to to their tents to rest prior to a full day of survey. The night sky cleared after the midnight hour, and a barred owl's call cut the silence of pre-dawn. It was the first species identified in what would be a very productive day of survey!

Daytime survey

With the sky beginning to brighten, the first order of business was tended to...birds. Staff, having camped at the bog, began work bright and early. The crew began surveying for birds prior to participants arriving. I departed for the mile-long trek across boulders and cobbles to meet the early morning arrivals near the campground store. Upon returning to the bog with participants in tow, we gathered to begin our question and answer session at the bog. We pondered the dynamics of water drainage, elevation, and topography, as well as the slow geologic changes that must occur in order to create the conditions necessary for a high elevation bog. We analyzed maps, gained our bearings, and moved toward discussions about "indicator" species...those plants that are unique to the bog. These are the plants you must look for if you want to find the bog. The conditions in the bog are just right for these plants, and in the absence of them, one can conclude they are no longer in the bog. So, we began to search for and investigate those species: silky willow, sphagnum moss, cinnamon fern, and tawny cottongrass. Participants stepped off of the small terrace that retains the bog on it's southeast side and onto the pillow-like surface of the thick sphagnum moss. After those basic qualities were absorbed by us all, we regrouped at basecamp to review protocols, divide the group into teams, and review the plan for the day.

It would be a day of birds, butterflies, ferns and flowering plants. 29 species of bird were either heard or seen. Comparatively, 28 species were observed on July 21. The afternoon produced a phenomenal show of raptors including red-tailed hawk, sharp-shinned hawk, Cooper's hawk, American kestrel and broad-winged hawk. The Cooper's hawk was observed diving after prey in Area I of the bog. Other large birds included the American crow, common raven, barred owl, and turkey vulture.

The bog was glowing

with golds, and teaming with white blooms, the beautiful blossoms of goldenrods, boneset, turtlehead and tawny cottongrass. The insects were literally going bonkers over the sheer amount of nectar available. A section of the bog toward the west end Area III is now dubbed "butterfly alley". It was a large and continuous show of boneset, aster, sneezeweed, and goldenrod flowers. 16 species of butterfly were common in "butterfly alley", with several unidentified skippers also occurring. The most remarkable butterfly discovery of the day was one account of a Leonard's Skipper. One butterfly expert noted that many butterfly enthusiasts wait a lifetime to get to see this one!

The dragonflies were moderately active, with clamp-tipped emerald being the easiest to observe. Several large spiders were found, including the shamrock spider and marbled orbweaver.

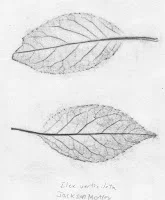

We are learning that ferns are a challenge, and that the best form of documentation is not a photograph, but an actual sample. With the help of our advisers we have been able to identify five fern species thus far, including crested wood fern and eastern marsh fern.

Laboratory Day

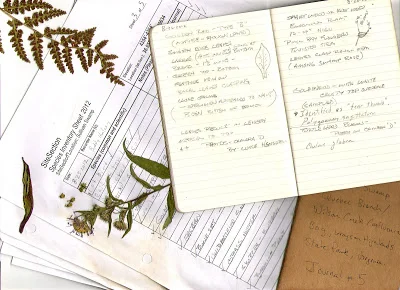

"Lab Day", as it is called, is an essential part of the SiteSection project. It is a day in which participants collaborate on refining their description of the ecosystem. It begins with uploading photographs and entering data collected in the field and identifying gaps in descriptions and species identification. Participants study collected specimens and photographs and perform research that includes using keys in guide books, searching online resources, and consulting with regional experts. Sketches, leaf rubbings and additional photographs may be produced during this process. Throughout the day the overall story of discovery from the prior day's survey is refined. The species list grows, the photographs are organized and shared in Facebook, and our interactive map for Sullivan Swamp is refined. Adults and youth alike work hard during this essential process. It is a time of rediscovery. Occasional eruptions of excitement occur as special species are identified, or as more questions arise.

The speed at which the youngsters could turn a photograph of a spider or insect into a positive identification was phenomenal. Jackson, Sawyer and Chase baffled us on several occasions. While some participants studied plant specimens with hand lenses, the high school aged participants swiftly navigated online resources to help narrow down plant species possibilities during the identification process. They used a variety of online resources including the Digital Atlas of Virginia Flora and USDA's plant database.

Three stations entered species names and notes into a common on-line spreadsheet. We use Google Docs (now Google Drive) so that multiple computers and users can work on the same document simultaneously. The species list link near the beginning of this blog article is the result of this collaboration.

On this occasion, as on others, the process of identifying species extended into the weeks beyond laboratory day. Even now, in late September, advisers are still pondering over a few unidentified species from the last outing.

With the changing of the seasons

, the cooling air, the shorter days, we look forward to the next survey outing. I'm excited just pondering the potentials of what might be discovered in mid October at Sullivan Swamp. Things will be different, that's for sure, and it will be the first time BRDC has explored this ecosystem in October. Stay tuned for survey results!

Survey Participants and Staff (left to right):

Devin Floyd (Program Director), Buddy Halsey, Lisa Benish

, Doug Moxley, Chase Hensdell, Carol Broderson, Jackson Moxley, Alex Benish, Sawyer Moxley, Vincent Benish, Luke Benish, Scott Jackson-Ricketts (Field Assistant), Bob Benish. Also present for survey and/or laboratory day were Eric Harold, Jane Floyd, Aaron Floyd (Site Data Manager), Cecelia Mathis,

Hardin Halsey,

Billy Mac Halsey, and Doris Halsey.

Special thanks also goes out to BRDC’s SiteSection program advisors: Rebecca Rader (fungi), Clyde Kessler (lepidoptera, general natural history), Bob Perkins (insects), Chip Morgan (ferns), and Doug Ogle (Mount Rogers area natural history, ecosystem, and flora expert).

Thank you Theresa Duffey, Natural and Cultural Resources Manager for the DCR, and Kevin Kelley, Chief Ranger at Grayson Highlands State Park for helping with permitting and site access.

Special thanks to the

Harris and Frances Block Foundation for funding this project. It would not be possible without their support!

-Devin Floyd, SiteSection Program Director, BRDC