A Journey to the Virginia Museum of Natural History

A fossil cast of the Giant Beaver (Castoroides ohioensis), constructed by VMNH paleontologists Alton Dooley, Raymond Vodden, and their students, that would have inhabited the saline marshes of Saltville during the Pleistocene. Unlike modern beavers that cut trees and construct complex structures, the animal fed peacefully on aquatic plants like a bear-sized muskrat.

Last week, between camps and the busy outreach programs of summer, the BRDC naturalists closed down the Center for a day and embarked on a road trip east across our beloved Blue Ridge Mountains, over the New River, and along the sprawling backroads, pinelands, and solar farms of the Southside region on a mission. What better way to inform our exhibit-making process than to learn how the state’s museum of natural history interprets flora, fauna, and fungi? Other earth sciences, included.

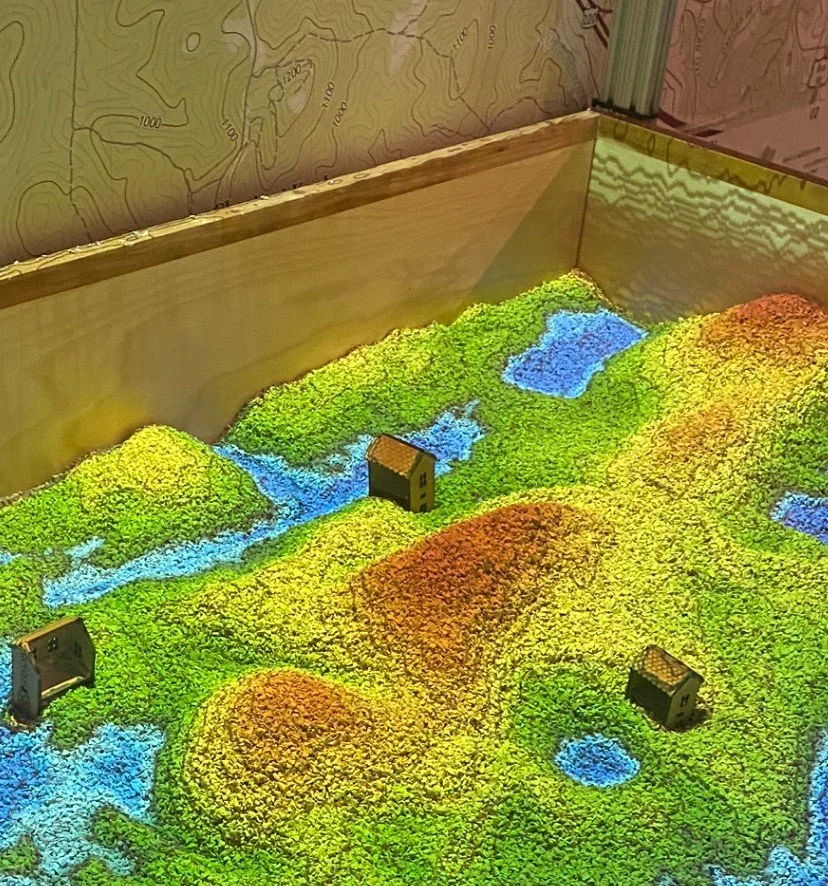

Our recreation of Whitetop Mountain, the Blue Ridge Discovery Center, K-Rock and Whitetop Station, including the surrounding watersheds on the VMNH interactive topographic map, a fun example of cartography for children of all ages.

We made it to Martinsville as the Virginia Museum of Natural History opened and spent the day exploring the exhibits. Exhibits varied from cultural and geological, to specific accounts of species found locally and abroad. The museum’s many maps, taxidermized specimens, and interactive exhibits were built for a much larger facility, but we took a plenty of ideas, notes and photos back with us. Each exhibit, from digitized displays for interchangeable insect collections to a paleontology lab complete with a field equipment flatlay, were added to our archive of brainstorming. A wide perspective is important as we begin construction on the new, public Visitor’s Center at Blue Ridge Discovery Center.

A Red-bellied Snake (Storeria occipitomaculata) we found beside a gravel road just before dusk.

After visiting the museum, Olivia graciously invited us to stay at her family’s cabin in the Ridge and Valley area along the Roanoke River. Big thanks to fellow naturalist Olivia Jackson and her family for enabling us to effectively make this trek to the museum. We had a cookout that evening and explored some Piedmont nature before returning to the Center the following morning.

Carboniferous fern fossils from the Grundy exhibit (Alethopteris sp.)

Interestingly, Southwest Virginia had a dominant presence throughout the museum. Compared to many other parts of the state, the museum featured the region prominently. The megafauna fossils of Saltville, and the Carboniferous fossils of Grundy coal seams each had their own specific exhibits, named for the towns. Interestingly, there was little to no recent natural history of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Southwest Virginia, despite the world-class biodiversity present here.

This changing exhibit featured the current and past researchers collaborating with the museum, relevant specimens, and information about their individual work. A version of this exhibit might be displayed at the Blue Ridge Discovery Center.

Not only did we gain ideas about how to share information about the greater Mt. Rogers ecosystem from the style of the museum’s exhibits, we also were able to learn what new and unique opportunities that the Blue Ridge Discovery Center can provide that are not displayed at this museum. Pursuing our mission to remain a world-class facility to teach about local natural history, we have the opportunity to build exhibits with “secrets” from the high-elevation Blue Ridge Mountains that the VMNH and other interpretive institutions have not yet displayed.

A Six-Lined Racerunner (Aspidoscelis sexlineata), that made an appearance at a blackberry-picking stop we made before crossing back into the Blue Ridge Mountains.