The Great Monarch Migration

Monarch tagging at our latitude begins August 29! They are about to embark on an incredible journey

Happy Bee-lated World Bee Day

World Bee Day was May 20th, a day to appreciate bees for the enormous role they play as pollinators.

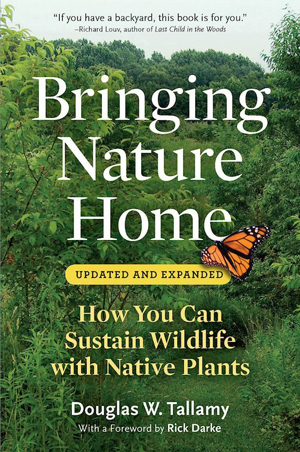

Bringing Nature Home

"Chances are, you have never thought of your garden — indeed, of all of the space on your property — as a wildlife preserve that represents the last chance we have for sustaining plants and animals that were once common throughout the U.S. But that is exactly the role our suburban landscapes are now playing and will play even more in the near future." Doug Tallamy

(August 2014) 5. The Living Landscape: Designing for Beauty and Biodiversity in the Home Garden, by Rick Darke & Doug Tallamy

For the August book(s), the BRDC Book Club has chosen: The Living Landscape: Designing for Beauty and Biodiversity in the Home Garden, by Rick Darke & Doug Tallamy. "A home garden is often seen as separate from the natural world surrounding it. In truth, it is actually just one part of a larger landscape that is made up of many living layers."

As a complimentary book we are also recommending: The New American Landscape: Leading Voices on the Future of Sustainable Gardening, edited by Thomas Christopher. "Gardeners are the front line of defense in our struggle to tackle the problems of global warming, loss of habitat, water shortages, and shrinking biodiversity"